It wasn't exactly love at first sight.

Massoud seemed willing enough to let me climb on his back, but when he had to get up with me clinging on for dear life he bellowed like he'd been shot. This didn't bode well. I'd heard all sorts of scare stories about camels. They smell, they spit, they are totally unpredictable. And this was just a half hour at camel school the day before, learning how to get on and off without getting tipped off. There's actually no real knack involved - once your camel has sat down on its haunches, stick your leg over and grab on to the top of the saddle.

Do not let go. A camel's legs seem to concertina under it as it sits down. When it gets up they unsheathe themselves up and backwards in two jolting movements. The effect on the rider is to shoot you skywards and then tip you forward so hard you're briefly staring vertically down at the ground over the top of your camel's head. Then the front legs unfold too and you're tipped back in the opposite direction so you think you'll fall over the back. And then suddenly you're high above the desert. Once you're up it's not so uncomfortable either. But then they don’t teach you what it’s like to engage first and pull away on your stead at camel school - that waits till the next morning when it's loaded up with rucksacks, tents, food and several bottles of (surprisingly drinkable) Tunisian wine. Well you didn’t think I'd spend the best part of a week in the Sahara without the odd glass of rouge, did you?

Read more > On the set of Star Wars in Tunisia

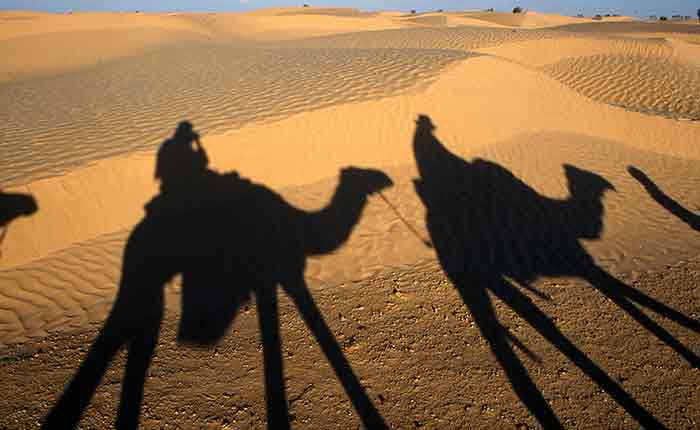

Maybe the extra weight meant Massoud was a little slower to lurch up off his knees the next morning? When we finally got under way the effect was surprising. It's immediately apparent why camels are called ships of the desert. Unlike horses, camels move front and back foot on the same side of the body forward together. This produces a very boat-like, side-to-side rocking motion. Four of us were looked after by one cameleer who owned the camels we were riding. He usually had one older wiser beast that led the group and the others were strung out behind - a rope through a ring in the side of the nose attaching each to the camel in front. We covered 15 to 20 miles a day and the cameleers walked the whole way. And then cooked us dinner over a campfire.

Saddled up, we headed off into desert.

The Sahara is not all dunes. Deserts have a whole array of scenery. On either side were small bushes of wiry scrub. The sand was gravel-like in consistency. The heat built fast. The smoothness of a breeze up there on camelback was vaguely soothing, but the sun's rays on exposed skin were like the slap of palm on legs. The vastness of the desert is all but your focus is restricted by the brim of your hat and the side of your sunglasses. Much of the concentration was about keeping track of the terrain for any unexpected bumps that might unseat you from your swaying mount.

Lunch in the sparse shelter of a bushy oasis brought home what an inhospitable place the desert is. We lay, breathing shallowly, smelling the sweat on our clothes, sand between our teeth and in our shoes, waiting for the sun's intensity to subside. But it stalked us, moving around our small bushes shifting the pools of shade, making us move every half hour or so. Around 3.30 we lumbered on. Sand dunes are strange things. I wondered how long it takes for those vast piles of sand to be amassed by the force of the wind. We were now far in the middle of wave upon wave of them. The ride was rollercoaster-like, Massoud would stride to the top of a dune, teeter briefly on top for a moment and then plunge crazily down the other side, his nose tugged by the rope connecting him to the camel in front. There was little time for either of us to admire the view.

Around 5.30 we stopped to make camp for the night. It was just a case of pick a dune and roll out your sleeping mat. The cameleers made fires and we helped hunt for wood. The small bushes that grow in the desert hold a minimum of moisture. They are living, but their branches snap like old rotten wood. The sun sets quickly. For 20 minutes the dunes were bathed in golden light and the sky was a deep turquoise blue. Then it was dark - and cold. We piled on clothes and sat around the fire. Mohammed was stirring a bubbling pot of stew and a huge round flat bread was baking away in embers on the sand nearby. We cracked open a bottle of wine and lay back and looked at the stars. When the moon arrived it was almost bright enough to read by.

Sand is not the most comfortable of sleeping surfaces. During the night the cold left me shivering. More flat bread, hot sweet tea and fig jam restored lost energy and we were off early in the cool of the morning. The early hours before 11 are perfect camel riding conditions. The light is warm and soft, the breeze has just a hint of chill. Little was said, as plonked in our own thoughts we lumbered along, watching the undulating sands dip and sway around and below. At lunch time, listening to the rhythmic chomping of a camel eating a palm tree, I drifted off to sleep in the shade. In the afternoon we stopped at an old village, still with working well. Odd to see water wound up from the depths in an old bucket surrounded by such dryness. Nearby was an old domed building called a Marabou - the final resting place of a wise old woman still apparently venerated by the local people.

The dunes and the days drifted into each other. The slow lumbering was soporific. I wondered how easy it would be to fall asleep on a camel. Slowly our trek brought us round in a loop to where we'd started. How the cameleers knew where we were I've no idea. On the last day the camel in front seemed to stop and eat from every bit of scrub we passed. And then it started. To begin with it was just small squirts of green stuff. The rest of the day he was chewing and pooing in unison.

Back where we'd first joined our camels, we were ready to climb down for the last time. And then the projectile stuff arrived. I'd had an inkling of what would happen. A camel with a dodgy stomach spins his tail around as he's ejecting the stuff, creating helicopter slime. The guy in front got covered. I discovered a new way to get off. Stick your feet over the side and jump! The closest of escapes.

That night, after the best shower in the world, we sat stiffly around a table in a restaurant, tired, rather sunburnt but pleased to have completed the trip. There was only one thing left to do. Eat camel couscous.

Fancy a camel safari?

Get There: Fly to Tunis with British Airways or Tunis Air.

Do The Tour: Exodus's 9 day Tunisia Explorer trip includes a camel trek into the Sahara and takes in many of Tunisia's ancient sites.

Find Out More: The Tunisia Tourist Board website.